It’s also worth diving into the way our relationship to risk outside of finance might play a role in planning and investing.

What is investing risk?

Risk in the real world means exposure to danger. It’s the same with investing, only the danger tends to be rather specific: losing money.

All investing carries this risk. You could lose your original investment. And while some investments are riskier than others, there’s no 100% safe investment.

So why do it? Because risk comes with the potential for reward, or a return on your investment. It’s the age-old risk-reward paradigm. And, as you might suspect, the potential for a bigger reward tends to carry more risk.

Plus, it’s worth noting that not investing carries risk, too. If you kept all of your money in cash, inflation would effectively chip away at its value. This loss of purchasing power is known as inflation risk.

Types of investment risk

Market risk refers to the risk of investing in financial markets overall. Market risk is also known as systemic risk; it’s the kind of risk that comes from the entire market (versus one segment of it) and can only be avoided by not investing. You may hear people talk about stock market risk or bond market risk, and the systemic risk included in those. This is the broadest type of investment risk.

Nonsystemic risk, in contrast, refers to risk that can be isolated from the market as a whole. For instance, if a certain company declares bankruptcy, the entire stock market generally isn’t at risk. Business risk refers specifically to the risk of investing in a single company. Many things can impact the health of a single company, from leadership to the weather. (When multiple companies experience a crisis, you might hear experts talk about concern that this will trigger systemic risk, in other words, that it will stop being isolated and jeopardize the market overall.)

Default risk refers to the possibility that a bond issuer will default on the interest payments or fail to repay the principal at maturity. If a company declares bankruptcy, for instance, they may miss an interest payment on outstanding debt. One reason U.S. Treasuries are viewed as a relatively safe investment is due to one fact: The U.S. government has never defaulted on its debt.

However, Treasuries may not be viewed as “safe” when you take inflation risk into consideration. The average historical rate of inflation is between 3-4%. If your Treasury investment is yielding less than that, your money is still losing purchasing power, even as it grows.

Interest rate risk is related to inflation and inflation risk. When rates increase (usually to combat inflation) the value of existing bonds falls—if you wanted to sell those bonds on the secondary market, you’d need to do so at a discount, since they pay a lower interest rate than newer bonds.

Liquidity risk refers to how accessible an investment is. For instance, property tends to carry liquidity risk because, if you needed to access the value of the investment, it requires time and work (either creating a line of credit tied to the property or selling). This is somewhat related to opportunity risk, otherwise known as opportunity cost: Every time you make an investment in something, you give up the opportunity to use that money for something else.

Geopolitical risk ties to global and political events, like the Russian invasion of Ukraine or even a standard presidential election.

How risky are you?

There are two primary metrics we use to measure risk: risk appetite and risk tolerance.

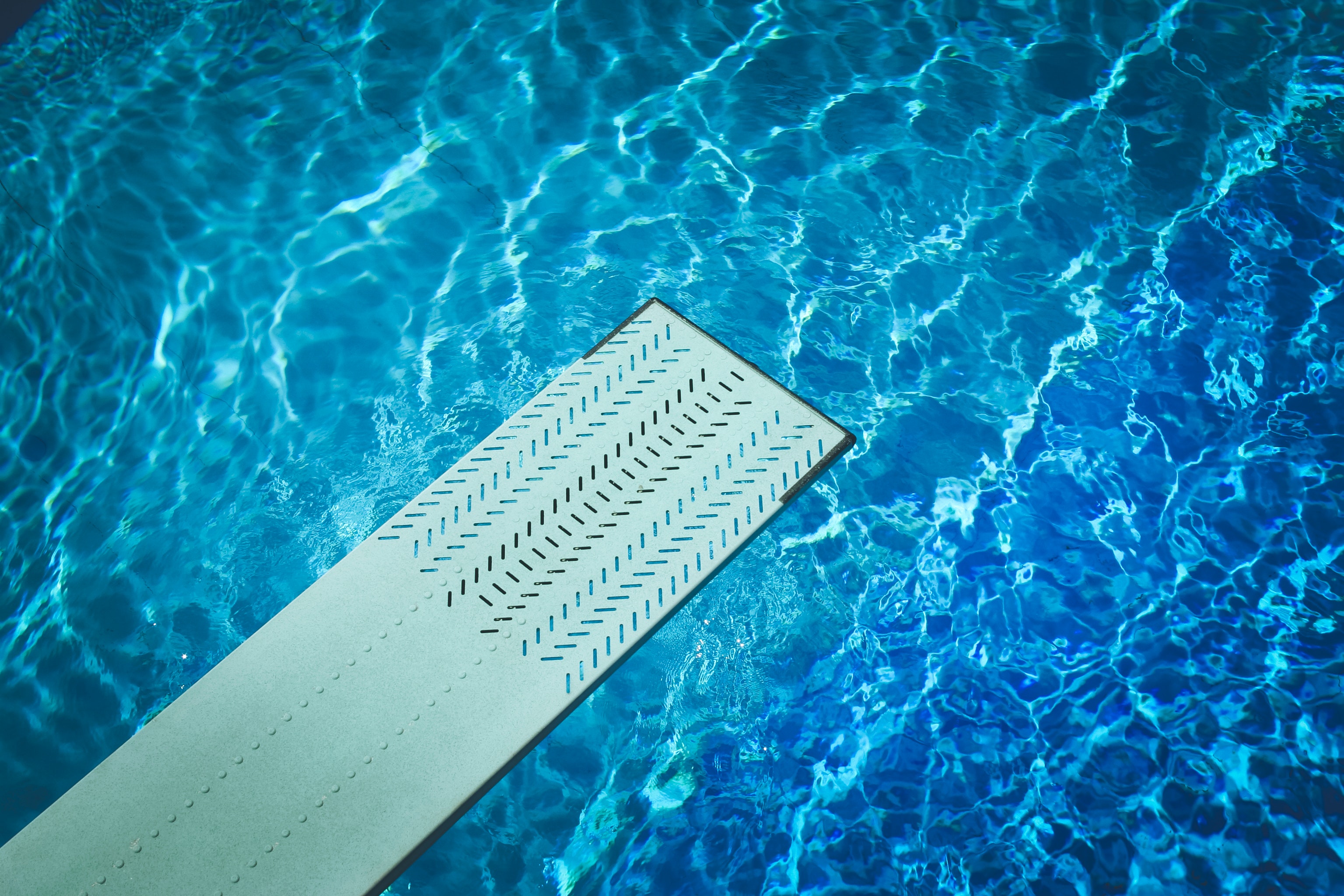

People tend to develop attitudes toward risk long before they think about investments. Some kids love the high dive while others prefer handstands in the shallow end. This attitude to risk can change over time or with circumstances. The 16-year-old who loved the high dive might have second thoughts at 61 after a knee replacement. Put another way, his risk tolerance might decrease with age, even if he still feels a thrill (or appetite) when he looks at a diving board.

We see this frequently in investing—someone starts out with a high appetite for risk, while their risk tolerance is ultimately a bit lower. We have a conversation with clients to help us understand where you fall in both of these categories. For example, we might ask you how you’d react if your portfolio lost 10-20% of its value tomorrow.

Investors with a high appetite for risk might buy the dip. But an investor who needs to access the funds in their portfolio within a year or two might be wondering if they need to find a safer investment. Their risk tolerance is lower.

When we look at clients’ risk tolerances, one of the first things we look at is time horizon. Investors with a longer time horizon can generally afford to take on more risk. The stock market posts positive returns on average, but it can take time for investments to bounce back.

Once we understand your risk, we look at your overall finances. Your overall assets (properties, businesses, collectibles, and the like) as well as any liabilities can impact your risk tolerance. Your financial obligations (such as dependents) can also play a role.

While it may seem strange to spend so much time attempting to quantify risk, this approach helps us get strategic about your portfolio. It helps remove emotion from investing. Your personal circumstances can also give us a more accurate benchmark for success; we’ll measure performance against your personal circumstances and goals instead of an arbitrary index.